Flexible and Performance-Based Design

Part 1 in a 3-part blog series showing how roadway design should control vehicle speeds, not speed limits.

So cars speed around your city, too? I bet you know of one or two racetracks disguised as roadways. I drive one every day, and I regularly see police officers pulling over the unexpecting victims of bad roadway design. I watch my speedometer driving that roadway to prevent from falling into the same speed trap with all the other vehicles. But, I have a confession – I’m more aware of speeding in my own neighborhood.

I don’t know about you, but I hear too many moral lectures shaming people who speed. To address the moral high ground of those lecturers, let’s uncover why we feel comfortable speeding on poorly design roads.

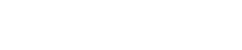

Driving on a freeway, you have one purpose – to get somewhere fast. We use the highway to be mobile and want the road to function with high mobility and speed. Conversely, when cars drive residential streets, we expect the cars to be slower, resulting in lower mobility. We select the roads we drive based on our purpose and needs. Traffic engineers assign a functional classification to reflect a road’s intended uses and the type of service it should provide; local roads provide low speed and mobility, while freeways and arterial roads offer high mobility and speed. The design of a road should reflect the functional classification and create different levels of movement and speed, but it doesn’t always come out that way.

If some is good, more isn’t better

Transportation engineers rely on manuals and guidebooks to determine minimum requirements for design. The American Association of State Highway Transportation Officials (AASHTO) produces and revises the go-to handbook A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets, affectionally called the “Green Book.” The problem with transportation minimum guidebooks, though, is they rarely provide a maximum. “Traditional application of this policy took the approach that, if the geometric design of a project met or exceeded specific dimensional design criteria, it would likely perform well. In some cases, leading to overdesign, constructing projects that were more costly and were inappropriate for the roadway context.” That’s not me talking – that’s inside the actual Green Book! (7th edition).

So, what does it mean to be “inappropriate for the roadway context?” Context is the location of the built roadway, and the 7th edition adds five context classifications for reference to frame the design: rural, rural town, suburban, urban, and urban core. The context classification provides design flexibility for the same type of road, whether it is built in the city or out of town. A significant contributor to Context is determining the design speed. For example;

- suburban collector streets should be 35-50 mph,

- urban collector streets are 30-40 mph, and

- urban core collector streets should be 25-30 mph.

A 5 mph difference in design speed may not appear significant. However, it changes several factors for stopping and sight distances, shoulder widths and clear zones, and horizontal and vertical curve designs. Rural collectors have the most significant window for design speed. They can be designed anywhere between a mountainous low-volume rural collector at 20 mph, to a level high-volume rural collector at 60 mph (GB 7th Ed. Table 6-1).

Table 6.1

Table 6.1

But here’s the kicker – a note in the Green Book indicates, “Where practical, design speeds higher than those shown should be considered” opening the door for roads designed for much higher speeds. When an urban collector road is recommended for speeds of 25-30 mph, but the actual design allows a large vehicle to operate at 40 mph comfortably – the natural speed limit becomes 40 mph or higher. As a result, we speed, regardless of the posted limits.

For more information on traffic control designs contact Scott Shea in our Transportation Division at (801) 494-9136 or scott.shea@crsengineers.com.